A Mead Recipe

Recently, I posted about my search for a Chinese mead recipe, and some potential leads.

Today, I cracked open the English-language textbook on Chinese food and beverage production, Science and Civilisation in China Volume 6 Biology and Biological Technology Part V: Fermentation and Food Science, and it contains a section on mead (page 246)!

It backs up my research so far, although it doesn't include the really early archaeological finds because they were excavated after it was published. There are a few mentions of honey used for various things in the classical period, but it isn't until the Tang dynasty in about 650 that we start to see references to mead.

The Song dynasty author Zhang Bangji (張邦基) recorded in his book Random Notes from the Scholar's Cottage (《墨莊漫錄》) what he claims is Su Dongpo's recipe for the mead mentioned in the poem I translated last time. Science and Civilisation has a translation, but I decided to make my own before I read theirs. It's in the fourth scroll, section 68:

My translation agrees pretty closely with the Science and Civilisation translation.

The recipe mixes weights and volumes, which means we need to be careful with the amounts we assign to them since it's not strictly proportional. Fortunately, Wang Li's dictionary has historical information on quantities. We want to know how big a jin, a liang, and a dou are, around 1100 CE, during the Northern Song dynasty. Su Dongpo wrote a little earlier than Zhang Bangji, but they were not so far apart.

During the Song dynasty, Wang Li gives us the following sizes:

1 jin is 16 liang, and based on archaeological finds a jin is about 633 g, so a liang is just under 40 g.

1 dou is 9.5 L

So, redacted, and rounding slightly, our recipe is:

Today, I cracked open the English-language textbook on Chinese food and beverage production, Science and Civilisation in China Volume 6 Biology and Biological Technology Part V: Fermentation and Food Science, and it contains a section on mead (page 246)!

It backs up my research so far, although it doesn't include the really early archaeological finds because they were excavated after it was published. There are a few mentions of honey used for various things in the classical period, but it isn't until the Tang dynasty in about 650 that we start to see references to mead.

The Song dynasty author Zhang Bangji (張邦基) recorded in his book Random Notes from the Scholar's Cottage (《墨莊漫錄》) what he claims is Su Dongpo's recipe for the mead mentioned in the poem I translated last time. Science and Civilisation has a translation, but I decided to make my own before I read theirs. It's in the fourth scroll, section 68:

東坡性喜飲,而飲亦不多。

|

It being the case that Dongpo’s nature was to like to drink, when he drank he did not drink many different things [possibly just “did not drink much”].

|

在黃州嘗以蜜為釀,又作《蜜酒歌》,人罕傳其法。

|

In Huangzhou he experimented with using honey to brew, and also wrote The Song of Mead, but people rarely share his method [for brewing].

|

每蜜用四斤煉熟,入熟湯相攪,成一斗,

|

For every four jin of honey, purified fully, put it into boiling water and dissolve it, to make up one dou.

|

入好麵曲二兩,南方白酒餅子米曲一兩半,

| |

搗細,生絹袋盛,都置一器中,

|

Grind until fine, put them in a newly-woven juan cloth [dense silk tabby] bag, and put everything in a single vessel.

|

密封之,大暑中冷下,稍涼溫下,天冷即熱下,

|

Seal it tight. In great heat cool it and in coolness warm it. If the weather is cold, then heat it.

|

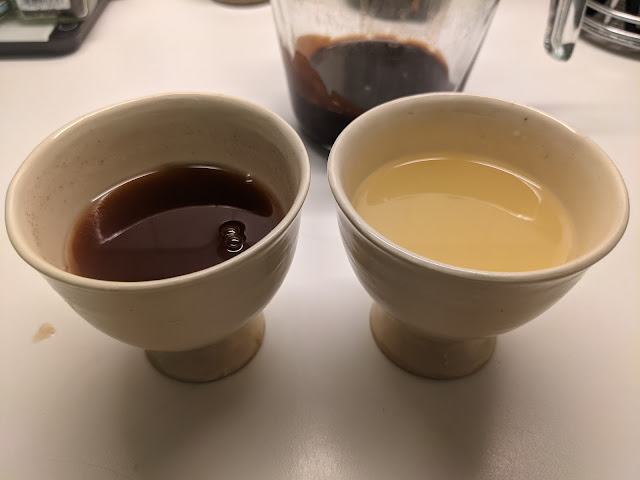

一二日即沸,又數日沸定,酒即清可飲。

|

In one or two days it will bubble, and after several more days the bubbling will stop. When the wine is clear you may drink it.

|

初全帶蜜味,澄之半月,渾是佳酎。

|

At first, it will keep the taste of honey, but after half a month of clarifying, it will be fine strong wine.

|

方沸時,又煉蜜半斤,冷投之尤妙。

|

Again adding half a liang of purified honey, cold, just when it begins to bubble is marvelous.

|

予嘗試為之,味甜如醇醪,善飲之人,恐非其好也。

|

I tried this myself, and the flavor was sweet like rich-tasting shortwine, but experienced drinkers may not enjoy it as much.

|

My translation agrees pretty closely with the Science and Civilisation translation.

The recipe mixes weights and volumes, which means we need to be careful with the amounts we assign to them since it's not strictly proportional. Fortunately, Wang Li's dictionary has historical information on quantities. We want to know how big a jin, a liang, and a dou are, around 1100 CE, during the Northern Song dynasty. Su Dongpo wrote a little earlier than Zhang Bangji, but they were not so far apart.

During the Song dynasty, Wang Li gives us the following sizes:

1 jin is 16 liang, and based on archaeological finds a jin is about 633 g, so a liang is just under 40 g.

1 dou is 9.5 L

So, redacted, and rounding slightly, our recipe is:

- 2.4 kg honey for the primary addition

- 20 g honey for the secondary addition

- Water to make up 9.5 L

- 80g good wheat yeast cakes

- 40g southern baijiu yeast cakes

And following the steps above, which are pretty straightforward. This is about a 1:4 honey:water ratio, which will make a medium strength mead at about 10-13% abv, give or take. That explains why the author thinks it's nice, but not strong enough for drinkers used to 15-20+% wine produced by staggered additions of rice.

Next time, we'll take a look at a recipe which might be from Su Dongpo himself!

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Comments

Post a Comment