Imperial-Style Thirst Water

I was trawling through a really large Yuan Dynasty cookbook The Compendium of Essential Arts for Family Living when I came across a section of recipes titled "thirst-waters." Curious, I read more.

The book says that these recipes are called, in foreign lands, 攝里白 which in reconstructed Middle Chinese is something like "syep li baek." A similar recipe I found in an anecdote in the 18th century Corrections to the Bencao Gangmu, relating a 14th century orchard of lemon trees planted by the Khan, says that the mongols call these drinks 舍里別 “syae li pjet.”

There's a category of Central- and West-Asian drinks that are fruit syrups dissolved into water called "sherbets," and that's indeed what these recipes are for. The earliest references I've found to thirst-waters in China date to the 12th century, where the Old Stuff from the Martial Forest lists, but does not give recipes for seventeen drinks named "cool waters":

It took me a while to track down Amomum villosum, but I found some eventually. It looks pretty different from cardamom, but smells similar, with a bit more camphor.

The "vine flower" is extremely ambiguous - pretty much exactly as ambiguous as it is in English. A conservative reading is probably "wisteria flowers:" if it were "purple vine" or "white vine," that'd be it.

That said, hops are also plausible. They're used in some yeast cake recipes in The Wine Canon of North Hill, and the method is strikingly similar to a hop bittering method for mead described in Chapter 22 of Olaus Magnus's 1555 CE A Description of the Northern Peoples, Volume 2:

That said, if the author had meant hops (蛇麻), why didn't they just say so? After all, North Hill calls them hops. Presumably the author had a specific plant in mind, and it seems unlikely they'd call hops "vine flower." I'd like to try this with wisteria flowers once they're available.

I think the malt in this is probably because the recipe author doesn't entirely understand what makes things ferment. There's a long history of being ambiguous about malt and yeast cakes in Chinese writing.

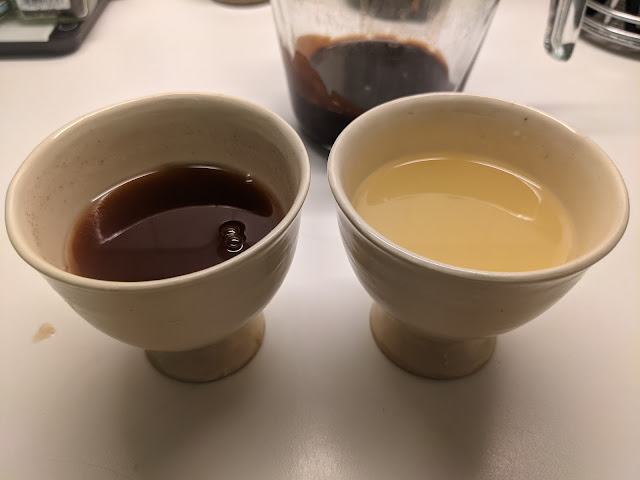

I made a batch and brought it to Brew U:

I actually really like the result. It's sweet, but the sweetness is strongly cut by the bitter hops and spices. It is rather a lot of hops, though - about 1 oz per gallon. Many tasters found it too bitter.

I had perhaps 8 oz of the mead left over, and I've put a new batch of honey on top of it. I'm hoping it'll turn into a nice dry, lightly spiced mead.

If you're curious about the Brewers' Guild paneling process, I've put my documentation up on the East Kingdom Wiki, so you can see how I structured things. There's a little more info there than in this post, but mostly it's just more rigorous citations and such.

The book says that these recipes are called, in foreign lands, 攝里白 which in reconstructed Middle Chinese is something like "syep li baek." A similar recipe I found in an anecdote in the 18th century Corrections to the Bencao Gangmu, relating a 14th century orchard of lemon trees planted by the Khan, says that the mongols call these drinks 舍里別 “syae li pjet.”

There's a category of Central- and West-Asian drinks that are fruit syrups dissolved into water called "sherbets," and that's indeed what these recipes are for. The earliest references I've found to thirst-waters in China date to the 12th century, where the Old Stuff from the Martial Forest lists, but does not give recipes for seventeen drinks named "cool waters":

- Sweet bean soup

- Coconut “wine”

- Bean flower water

- Pyrus calleryana broth

- Brined Prunus mume water

- Ginger honey water

- Chinese quince [Chaenomeles speciosa] water

- Tea water

- Aquilaria wood water

- Litchi paste water

- Bitter water

- Golden tangerine rounds

- Snow-foam strained skin drink

- Prunus mume flower wine

- Vietnamese balm [Elsholtzia ciliata] drink

- Five-ling [name for a variety of plants including cocklebur and licorice] greatly soothing solute

- Shiso [Perilla frutescens] drink

- Pounded young crabapples, boiled until the liquid has all their flavor. The liquor is boiled down to a syrup.

- Chinese strawberry juice, strained, simmered down to a syrup, and maybe sweetened with honey or rock sugar.

- Chinese quince pulp, sliced thin, boiled in honey for 4-6 hours. "Should form flexible strands."

- Five-Flavor Berries, soaked in boiling water overnight, and then the juice is simmered and colored with soy milk. Honey is added, and then simmered more.

- Grape juice boiled down. "You may make wine with it," which is interesting. Honey optional.

All of these were seemingly intended to be diluted into possibly-iced water as a refreshing drink on a hot day.

The sixth thirst-water calls for "conifer sugar" and a bunch of herbs, and I don't totally understand what it's talking about.

The very first entry, though, is rather different. It's a short mead:

渴水番名攝里白

| |

御方渴水

|

Imperial Style Thirst-Water

|

官桂 丁香 桂花

|

Cinnamon [Cinnamomum cassia], clove [Syzygium aromaticum], Osmanthus flowers [Osmanthus fragrans]

|

白豆蔻仁 (石宿)砂仁各半兩

|

Cardamom [Elettaria cardamomum] meat, (stone house), fructus amomi [Amomum villosum] each two liang.

|

細曲 麥蘗各四兩

|

Fine yeast cakes, wheat/barley malt [possibly barm], each four liang.

|

右為細末。用藤花半斤蜜十斤煉熟。新汲水六十斤。用藤花一處鍋內熬至四十斤。生絹濾淨用小口甏一個。生絹袋盛前項七味末。下入甏。再下新水四十斤。並巳煉熟蜜。將甏口封了。夏五日。秋春七日。冬十日熟。若下腳時春秋溫夏冷。冬熱

|

Grind fine with a stone. Take half a jin of vine [Dalbergia parviflora? Wisteria? Hops?] flowers, ten jin of well-refined honey. Sixty jin of newly-drawn water. Take the vine flowers, and after a moment in the wok, simmer it to 40 jin. Strain through a new dense plain-weave silk cloth into one small-mouthed jar. Fill a new dense plain-weave silk cloth bag with the above seven flavor powders. Then add it to the jar. Then, add 40 jin of new water. Then add the already-refined honey. Seal the jar’s mouth. In summer, five days. In fall or spring, seven days, in winter, ten days. If you have leftovers, warm it in spring or autumn, cool it in summer, and heat it in winter.

|

It took me a while to track down Amomum villosum, but I found some eventually. It looks pretty different from cardamom, but smells similar, with a bit more camphor.

|

| Spiky balls on left are Amomum, hulled and unhulled. To its right is a cardamom pod, and its seeds. Top is the osmanthus flowers, and the cloves. Powdered cinnamon on the separate dish. |

|

| All the powdered ingredients together. |

That said, hops are also plausible. They're used in some yeast cake recipes in The Wine Canon of North Hill, and the method is strikingly similar to a hop bittering method for mead described in Chapter 22 of Olaus Magnus's 1555 CE A Description of the Northern Peoples, Volume 2:

... an appropriate quantity of hops should be boiled separately in a linen bag inside a covered pot over the same fire, until at least half the water has evaporated, so that their bitterness may be evident.Emphasis mine.

That said, if the author had meant hops (蛇麻), why didn't they just say so? After all, North Hill calls them hops. Presumably the author had a specific plant in mind, and it seems unlikely they'd call hops "vine flower." I'd like to try this with wisteria flowers once they're available.

I think the malt in this is probably because the recipe author doesn't entirely understand what makes things ferment. There's a long history of being ambiguous about malt and yeast cakes in Chinese writing.

I made a batch and brought it to Brew U:

Recipe

For about 1 gallon. The original recipe is fifteen times this, fermenting 50 liters of water.- 5.33g each of cassia cinnamon, clove, osmanthus flowers, cardamom (shelled) and Amomum villosum (shelled)

- 10.67g each of fine yeast cakes and malted barley (I used six row)

- 21g hops (I used pellet Saaz due to my LHBS not having any leaf noble hops, and figuring that leaf Cascade would be farther from period than pelletized Saaz)

- 422g wildflower honey

- Brush yeast cakes clean, and break off an appropriately sized chunk, about 1” square.

- Bring 2.4L of water to a boil in a pot. Add the hops, and boil until it is reduced to 1.67L, about an hour. Let cool until bearable.

- While boiling, grind spices, yeast cakes, and malted barley to a fine powder in a mortar.

- Strain hop liquor through a fine cloth. Discard hop residue.

- Add another 1.67L water to the hop liquor, and the honey. Mix well.

- Place ground ingredients in a heavy silk bag. Pour wort into a 1 gallon wide-mouth fermenter, add the bag, and let ferment for five days at room temperature.

- Remove bag and serve immediately.

|

| Silk bag. Hand-sewn because of course that's how I spent my Monday night. |

This came out to 2.7% ABV for me, and kept fermenting the whole while. The yeast cakes I use don't seem to start fermenting very quickly, so it wasn't until a few days in that they really took off.

I actually really like the result. It's sweet, but the sweetness is strongly cut by the bitter hops and spices. It is rather a lot of hops, though - about 1 oz per gallon. Many tasters found it too bitter.

I had perhaps 8 oz of the mead left over, and I've put a new batch of honey on top of it. I'm hoping it'll turn into a nice dry, lightly spiced mead.

If you're curious about the Brewers' Guild paneling process, I've put my documentation up on the East Kingdom Wiki, so you can see how I structured things. There's a little more info there than in this post, but mostly it's just more rigorous citations and such.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Comments

Post a Comment